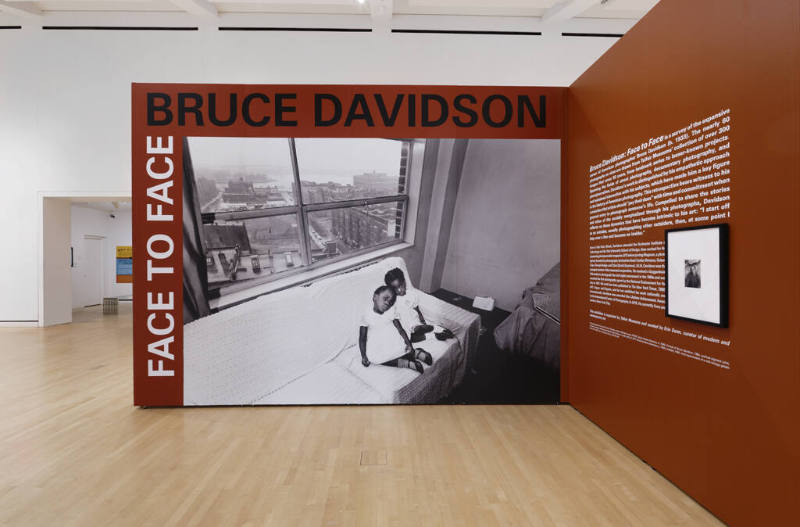

Bruce Davidson: Face to Face

Born in Oak Park, Illinois, Davidson attended the Rochester Institute of

Technology and the Yale University School of Design, then worked for the

pioneering photojournalist magazine LIFE before joining Magnum, a photo agency founded by photography luminaries Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger, and Chim (David Seymour). At 24, Davidson was the youngest member of the renowned cooperative. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph the civil rights movement in the 1960s and was awarded the first photography grant by the National Endowment for the Arts in 1967. His work has been published in The New York Times, TIME, LIFE, Vogue, and Esquire, and he has exhibited his work nationally and internationally. Davidson was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the

International Center of Photography in 2018. He currently lives and works in New York City.

This exhibition is organized by Telfair Museums and curated by Erin Dunn, curator of modern and contemporary art.

CAREER

BEGINNINGS

The early years of Davidson’s career are marked by personal projects invested in portraying the lives of sidelined individuals or communities. The intimate, black-and-white closeups of Madame Fauché, the widow of impressionist painter Léon Fauché in Paris, the clown Jimmy Armstrong in the Beatty Clyde circus, and the rebellious teenage gang known as “The Jokers” in Brooklyn speak to Davidson’s closeness with his subjects and his endeavor to bring their narratives to the forefront.

In the 1966 press release for Davidson’s first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), John Szarkowski, director of the museum’s photography department, commented:

Few contemporary photographers give us their observation so unembellished—so free of apparent craft or artifice—as does Bruce Davidson. In his work, formal and technical concerns remain below the surface, all but invisible. The presence that fills these pictures seems the presence of the life that is described, scarcely changed by its transmutation into art.

This assessment of Davidson’s work at the beginning stages of his profession–he was 33 at the time of Szarkowski’s statement–has remained a consistent refrain throughout his 70-year career.

SOCIAL

CHANGE

Dissatisfied with fashion assignments from Vogue and prescribed photo essays in LIFE, Davidson felt a strong pull to document racial and social injustice in the 1960s. After receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship to explore “Youth in America,” he traveled south between 1960 and 1965 to record young people protesting, marching, and participating in freedom rides and sit-ins for equal rights. Reflecting on the contemporary impact of Davidson’s photographs, the late civil rights icon Congressman John Lewis said: “Bruce’s courageous photographs helped to educate and sensitize individuals beyond our Southern borders. They shone a national spotlight on the signs, symbols, and scars of racial segregation.”

In 1967, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded Davidson its first grant for photography, funding a project to photograph the low-income communities of predominantly Puerto Rican and African American families living in the dilapidated tenement houses in a section of East Harlem. Returning day after day for two years, Davidson fostered relationships with the families living in the neighborhood with the help of Metro North Association, a neighborhood advocacy group. The association used his photographs as evidence of the poor living conditions to seek and secure funding for improvement from city officials. Today, Time of Change and East 100th Street speak to the power of photography not only as a witness to history, but as a catalyst for urgent change.

NEW YORK

CITY

New York City has proved fertile ground for many of Bruce Davidson’s best-known series. After his work in Brooklyn in the late 1950s and in East Harlem in the late 1960s, Davidson engaged with other communities in the city. In 1973 and again in 1990, he traversed the Lower East Side with Jewish-American author Isaac Bashevis Singer, who introduced him to favorite local spots in the Jewish community, such as the Garden Cafeteria, a diner where Holocaust survivors congregated to tell their stories. In 1980, he traveled underground to explore the simultaneous beauty and grime of the subway system, which brings people of all walks of life together. During the 1990s, he traversed the few blocks from his home to the landscaped environment of Central Park–a haven of nature in a city of concrete–to witness the democratizing and revelatory modes of human behavior. A declared humanist, Davidson is interested in people and their contexts and how they live their lives, a fascination he believes also tells him something about himself. His constant striving for self-discovery in his home city helps him communicate the myriad stories and cultures he uncovers.

TRAVEL

Although Bruce Davidson is principally associated with New York City, his profession frequently took him across the United States and abroad. In 1964, Esquire requested Davidson photograph Los Angeles for an upcoming feature. At the time, his cynical take on the superficiality he encountered in the city resulted in the magazine returning the photographs without comment. Revisiting LA between 2008 and 2013, Davidson’s critical eye softened at the beauty of its diversity of plant life–from the towering palm trees to the ivy climbing the underside of the Glendale freeway interchange–nature striving to survive in the fast-paced environs. Similarly, while his 1950s trip to Paris resulted in nostalgic reflection through the figure of Madame Fauché, his 21st century sojourns to the city considered the surrounding lushness of the natural environment. Even in the past few decades, when Davidson has turned his attention beyond people in a particular location to the features of the natural world, keen observation of the overlooked or unnoticed remains a consistent signature of his work.